Abstract

Pavement burns are common in a dry high heat climate. This study reviews the etiology, management, and outcome pavement burns in children. All patients age <18 who sustained contact burns from hot pavement from January 1, 2014 to December 31, 2019 were reviewed for mechanism, medical history, treatment course, and outcome. The high ambient temperature on each date and zip code of each injury were extracted from Weather Underground (www.wunderground.com). In this study, 45 patients met criteria and were reviewed 27 patients (60%) were male. Average age was 3.29 years (SD 0.69), made up two discrete age groups: age 3 years and under (n = 40, 89%) and older patients 14 years of age and up (n = 5, 11%). Thirty-eight patients (84%) had no known medical history. All had second-degree burns and one patient (2%) also had third-degree burns. Mean TBSA was 2.5% (SD 1.4%, range 0.75%–5.5%). Burn etiology included 31 patients (69%) who were walking barefoot on pavement, six (13%) who fell onto pavement, one (2%) seizure, and other/unknown etiology for the remaining seven patients (16%). Thirty patients (67%) had injuries on the plantar aspect of the bilateral feet, two (4%) to bilateral palms of hands, four (9%) to other parts of upper extremities, and 10 (22%) to other parts of lower extremities. Thirty-four patients (76%) were managed without any hospitalization. Those that were hospitalized had an average length of stay of 2.72 days (range 1–9 days). All burns were managed nonoperatively with topical therapy alone. Thirty-four patients (76%) were managed initially with silver sulfadiazene alone and six (13%) with bacitracin alone. Aquacel dressing was utilized in 10 patients at a follow-up visit (22%). Three patients (6.7%) were treated with collagenase enzyme therapy at some point in their care. One patient developed a superficial infection requiring oral antibiotic therapy. There were no mortalities in this group. High ambient temperature on date and location of each injury was 102.1°F (SD 5.4°F, range 89–111°F). Of the 30 patients that continued to follow up in clinic the average time to the burn being 95% healed was 10.50 days (SD 8.97 days, range 2–40 days). Pavement burns in children are partial thickness and are safely managed with topical therapy alone with good outcomes. Patients age 3 and under are at high risk.

In children, scald and flame burns represent the vast majority of burn etiologies in this age group.1 Contact burns from hot pavement comprise a small percentage of burns nationwide but are a common cause of burn injury in a hot desert environment, especially during the summer months. Continuous direct sunlight combined with radiant heat absorption can cause the asphalt surface temperature to rise to a level much higher than the ambient temperature.2 When the ambient temperature rises to 100°F, the asphalt can heat up to 131°F, and when the ambient temperature goes to 104°F, the asphalt can heat up to 150°F. Under these circumstances, one can sustain a second-degree burn in less than 35 seconds.2 Our institution has demonstrated that pavement burn admissions rise precipitously once the ambient temperature exceeds 95°F.3

In adult patients, when pavement burns are compared to flame or scald burns of similar size, they require increased length of stay, need for operative intervention, and higher overall costs.3 When performing a deeper analysis of pavement burns, the most common causes in adults included being found down on pavement, walking on pavement, mechanical fall, syncopal fall, and seizures.4 Many patients had peripheral neuropathy or cognitive dysfunction, which limited their ability to detect that they were sustaining a burn injury while walking on a hot pavement surface. About half required some type of operative intervention.4

This study focuses on pediatric patients defined as 18 years of age or younger. This study aims to determine the mechanisms, injury patterns, and management of pavement burns in children, and note the differences in this burn mechanism between adults and children, using what has already been demonstrated in the literature for adults.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective review was performed on the burn registry at our ABA verified Burn Center for patients 18 and under who sustained pavement burns between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2019. Data were collected on date of injury, date of birth, gender, total body surface area, body part injured, hospital length of stay, etiology, depth of burn, topical therapy, operative vs nonoperative management, past medical history, and zip code of injury. High ambient temperature was determined from Weather Underground (www.wunderground.com) on each date based on the zip code of each injury. Statistical analysis was done using Stata Version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). This project was approved by University Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

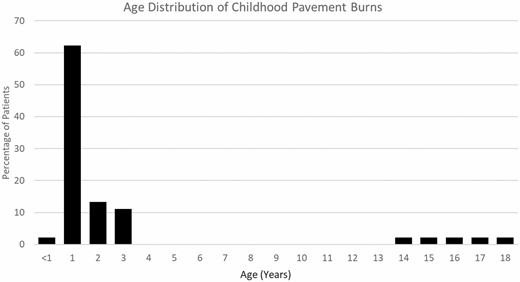

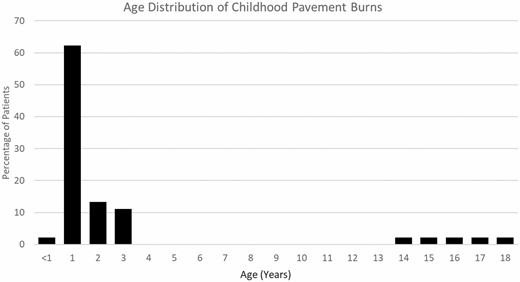

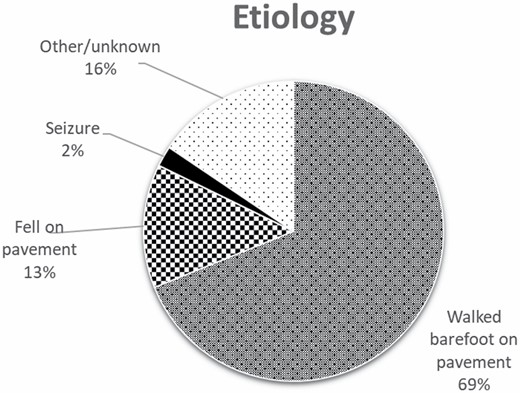

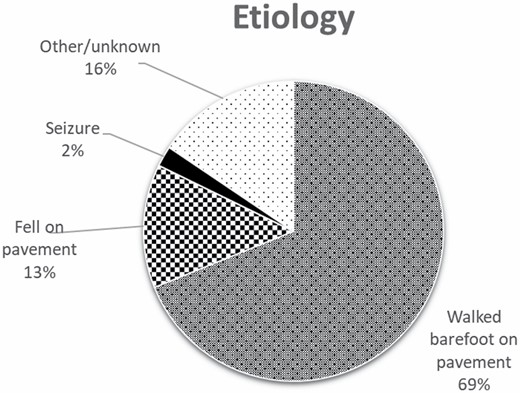

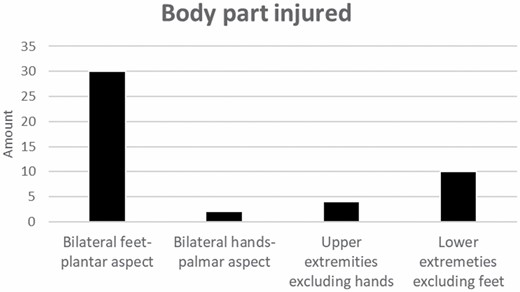

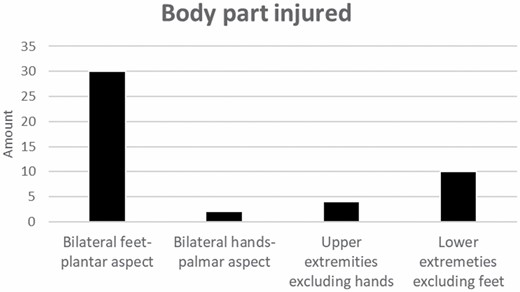

A total of 45 patients were identified for this study period and met inclusion criteria. Twenty-seven patients (60%) were male. The average age of the patients was 3.29 years (SD 0.69) (Table 1). Age distribution was composed of two discrete age groups: age 3 and under (n = 40, 89%) and 14 years of age and older (n = 5, 11%) (Figure 1). All 45 patients had second-degree burns and one also had a third-degree burn. The mean TBSA was 2.5% (SD 1.4%, range 0.75%–5.5%) (Table 1). The leading cause of burn injuries in this population was walking barefoot on pavement at 69% followed by falling onto pavement (13%), seizure (2%), and other/unknown etiology (16%) (Figure 2). The most common location of injury was the plantar aspect of bilateral feet (65%). Other injured locations included lower extremities excluding the feet (22%), palmar aspect of bilateral hands (4%), and upper extremities excluding the hands (9%) (Figure 3). Twenty-nine of the 30 patients (97%) who had burned the plantar aspect of their bilateral feet were 3 years of age or younger.

Summary of demographics, clinical features, and management of pediatric pavement burns

| n = 45 | |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 27 (60%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 3.29 (4.61) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 1.58 (1.25–2) |

| TBSA%, mean (SD) | 2.5% (1.4%) |

| Second-degree burn, n (%) | 45 (100%) |

| Third-degree burn, n (%) | 1 (2%) |

| Hospitalized, n (%) | 11 (24%) |

| Hospital LOS (median, IQR) | 2 (1–4) |

| Surgery, n (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Topical antimicrobials, n (%) | 41 (91%) |

| Enzyme debridement, n (%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Systemic antibiotics, n (%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Days to 95% healed, mean (SD) | 10.5 (8.9) |

| Days to 95% healed, median (IQR) | 8 (4–14) |

| n = 45 | |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 27 (60%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 3.29 (4.61) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 1.58 (1.25–2) |

| TBSA%, mean (SD) | 2.5% (1.4%) |

| Second-degree burn, n (%) | 45 (100%) |

| Third-degree burn, n (%) | 1 (2%) |

| Hospitalized, n (%) | 11 (24%) |

| Hospital LOS (median, IQR) | 2 (1–4) |

| Surgery, n (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Topical antimicrobials, n (%) | 41 (91%) |

| Enzyme debridement, n (%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Systemic antibiotics, n (%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Days to 95% healed, mean (SD) | 10.5 (8.9) |

| Days to 95% healed, median (IQR) | 8 (4–14) |

Summary of demographics, clinical features, and management of pediatric pavement burns

| n = 45 | |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 27 (60%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 3.29 (4.61) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 1.58 (1.25–2) |

| TBSA%, mean (SD) | 2.5% (1.4%) |

| Second-degree burn, n (%) | 45 (100%) |

| Third-degree burn, n (%) | 1 (2%) |

| Hospitalized, n (%) | 11 (24%) |

| Hospital LOS (median, IQR) | 2 (1–4) |

| Surgery, n (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Topical antimicrobials, n (%) | 41 (91%) |

| Enzyme debridement, n (%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Systemic antibiotics, n (%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Days to 95% healed, mean (SD) | 10.5 (8.9) |

| Days to 95% healed, median (IQR) | 8 (4–14) |

| n = 45 | |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 27 (60%) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 3.29 (4.61) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 1.58 (1.25–2) |

| TBSA%, mean (SD) | 2.5% (1.4%) |

| Second-degree burn, n (%) | 45 (100%) |

| Third-degree burn, n (%) | 1 (2%) |

| Hospitalized, n (%) | 11 (24%) |

| Hospital LOS (median, IQR) | 2 (1–4) |

| Surgery, n (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Topical antimicrobials, n (%) | 41 (91%) |

| Enzyme debridement, n (%) | 3 (6.7%) |

| Systemic antibiotics, n (%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| Days to 95% healed, mean (SD) | 10.5 (8.9) |

| Days to 95% healed, median (IQR) | 8 (4–14) |

Figure 1.

Age distribution of pediatric pavement burns.

Figure 1.

Age distribution of pediatric pavement burns.

Figure 2.

Etiology of pediatric pavement burn.

Figure 2.

Etiology of pediatric pavement burn.

Figure 3.

Body part injured.

Figure 3.

Body part injured.

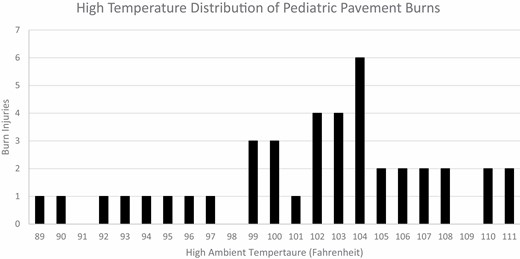

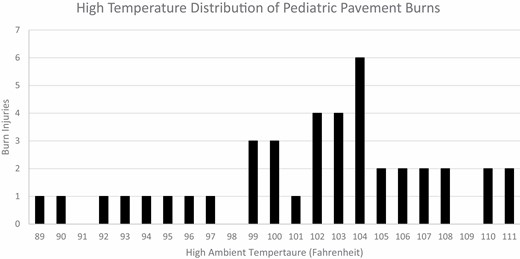

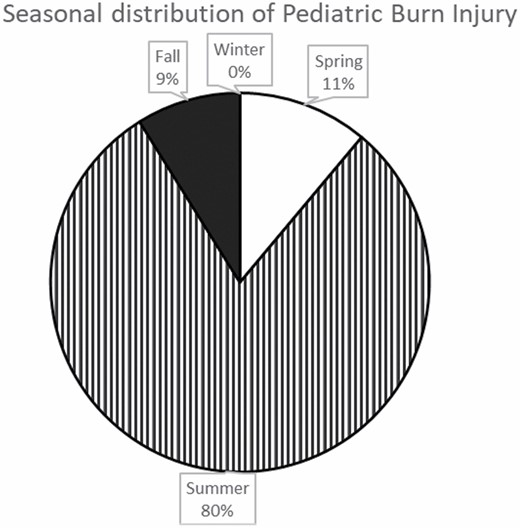

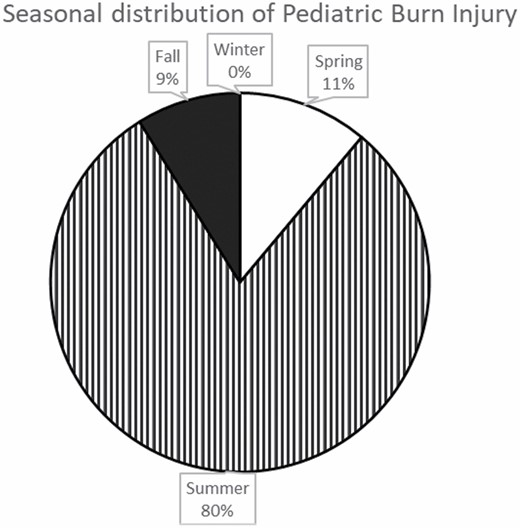

The average high ambient temperature on date and geographic location of each injury was 102.1°F (SD 5.4°F, range 89–111°F). Thirty-four of these injuries (76%) occurred when the high ambient temperature on the day of injury was 99°F or higher (Figure 4). Thirty-six (80%) of the injuries occurred during our Summer season (June/July/August), followed by five (11%) during the Spring (March/April/May) and four (9%) during the Fall (September/October/November). None sustained injuries in the Winter (December/January/February) (Figure 5). Two patients had unclear documentation as to the geographical location of their injuries and were excluded from this analysis.

Figure 4.

High ambient temperature distribution of pediatric pavement burns.

Figure 4.

High ambient temperature distribution of pediatric pavement burns.

Figure 5.

Seasonal distribution of pediatric pavement burn injuries. The following are seasonal distributions: Winter (December to February), Spring (March to May), Summer (June to August), and Fall (September to November).

Figure 5.

Seasonal distribution of pediatric pavement burn injuries. The following are seasonal distributions: Winter (December to February), Spring (March to May), Summer (June to August), and Fall (September to November).

All burns were managed nonoperatively with topical therapy alone and 34 patients (76%) were managed completely on an outpatient basis. Thirty-four patients (76%) were managed initially with silver sulfadiazene alone, six (13%) with bacitracin alone, and one (2%) with bacitracin in combination with collagenase (Table 2). One patient had a hybrid therapy with included silver sulfadiazene to the hands and bacitracin to the knees. Another patient presented for their first visit and had already epithelized their burns and was treated with lotion alone. Two patients treated with silver sulfadiazene had burns that deepened, which prompted a transition of therapy to topical enzymatic debridement with collagenase. One of those two patients developed a right palm contracture that was treated with occupational therapy, compression, and silicone and did not lead to any functional limitations. Aquacel dressing was utilized in 10 patients at a follow-up visit (22%). Three patients (6.7%) were treated with collagenase enzyme therapy, either initially or further into their treatment course. One patient developed a superficial infection requiring oral antibiotic therapy. There were no mortalities in our study population.

Initial management of pediatric pavement burns

| Initial Management | N = 45 |

|---|---|

| Silver sulfadiazene alone | 34 |

| Bacitracin alone | 6 |

| Silvadeine & bacitracin | 1 |

| Collagenase & bacitracin | 1 |

| Acticoat | 1 |

| Dry sterile dressing | 1 |

| Lotion | 1 |

| Initial Management | N = 45 |

|---|---|

| Silver sulfadiazene alone | 34 |

| Bacitracin alone | 6 |

| Silvadeine & bacitracin | 1 |

| Collagenase & bacitracin | 1 |

| Acticoat | 1 |

| Dry sterile dressing | 1 |

| Lotion | 1 |

Initial management of pediatric pavement burns

| Initial Management | N = 45 |

|---|---|

| Silver sulfadiazene alone | 34 |

| Bacitracin alone | 6 |

| Silvadeine & bacitracin | 1 |

| Collagenase & bacitracin | 1 |

| Acticoat | 1 |

| Dry sterile dressing | 1 |

| Lotion | 1 |

| Initial Management | N = 45 |

|---|---|

| Silver sulfadiazene alone | 34 |

| Bacitracin alone | 6 |

| Silvadeine & bacitracin | 1 |

| Collagenase & bacitracin | 1 |

| Acticoat | 1 |

| Dry sterile dressing | 1 |

| Lotion | 1 |

Of the 11 individuals (24%) managed as inpatients, the admission criteria included pain control, monitoring of wound progression, and/or seizure workup. One patient was admitted for both pain control and for wound monitoring. Two patients had seizures simultaneously sustaining burns on the pavement which warranted an admission to run further diagnostic studies. Two were admitted for unknown reasons. Hospitalized patients had an average length of stay of 2.72 days (range 1–9 days).

Overall we had 30 (67%) patients who continued to follow up at our burn center for the completion of their care. The mean time to 95% burn wound healing for these patients was 10.5 days (SD 8.9 days). Of the 15 patients lost to follow up in our burn clinic, two moved out of state after their last visit in our clinic. Both of these patients were treated with Aquacel dressing with good adherence on their last clinic visit. Two other patients returned to our hospital for a nonburn problem. One returned 12 days after her last clinic visit with the burn epithelized and the other presented 6 months after his last clinic visit with complete closure of his burn wound.

Discussion

Pavement burns are responsible for a significant number of burn injuries in a desert climate especially during periods of high heat and sun exposure. As pavement and other sun-exposed surfaces absorb radiant heat the temperatures increase dangerously high levels. Individuals can sustain a second- or third-degree burn in seconds.2 Our center has demonstrated a surge of pavement burn admissions whenever the ambient temperature rises above 95°F.3 This current study shows that the overwhelming majority of pediatric pavement burns occur once the temperature rises to 99°F or above.

Our institution has shown that pavement burns in adults are more severe compared to equivalent sizes of scald and flame burns. They require increased hospital length of stay, resource utilization, and operative intervention.5,6 Patients at increased risk for such burns include those who are found down on the pavement, walking on pavement, sustain mechanical or syncopal falls, and those who fall on the pavement while having a seizure.4 Additional risk factors include severe diabetic peripheral neuropathy resulting in patients not being able to feel their feet being burned while walking on a very hot pavement surface.4,7

Our analysis of pediatric pavement burns challenges conventional wisdom ascertained from analysis of adults. Pavement burns in children are far less severe than in their adult counterparts. They are more superficial and their average TBSA is much smaller. Consequently, they can be managed safely nonoperatively and with most burns successfully being treated exclusively in the outpatient setting. Unlike pavement burn in adults where there was a scattered distribution of body parts injured, this study demonstrates that almost two-thirds of the pediatric patients in our data set injured the plantar aspect of bilateral feet.4 This correlates with the most common etiology of walking barefoot on hot pavement. We believe that many of these burn injuries were from very young children who were walking unsupervised without proper footwear on the pavement. Once they felt the pain of walking on such a hot surface they immediately sought cooler surfaces and/or their guardian heard them crying and came to their rescue. This is different from adults, many of whom are burned after spending extended time periods exposed to hot pavement from neuropathy or physical incapacitation.

Similar to adults, the patients in this study group sustained injuries during the summer when the ambient temperature is extremely high on a near daily basis. This puts toddlers, who are ambulatory but not aware of the risks of the hot pavement, vulnerable to acquiring a burn in just a matter of seconds. This phenomenon is not dissimilar to toddlers who are unaware of dangers, and can be injured by falling down stairs or into swimming pools. While their injuries are more forgiving than in adults, the need for public awareness is no less imperative. These findings will be used to expand public awareness campaigns already established by our center. This includes collaboration with local pediatricians to provide basic education to parents of young children regarding the hazards of hot pavements surfaces heading into the summer season. We plan on using this data to reinforce with our EMS colleagues and local media partners on the importance of issuing high heat alerts when the temperature rises to or above 95°F. This study stresses the need for continued education focused on injury prevention, devotion of resources on pavement burns at large, and surging of staff during the summer seasons to meet the increased demands.

Our study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective review which comes with weaknesses that are inherent to the nature of such a study. Second, it is a single-center study and as a result the findings may not necessarily be reproducible at other burn centers. Third, about one-third of the patients were lost to follow up in our burn clinic. As stated earlier, two patients relocated while being treated with Aquacel dressing with good results. Two other patients returned to our hospital for an unrelated medical problem and at the time of presentation, their burns had healed. For the remaining 11 patients are concerned, their burn wounds were also healing appropriately and were quite minimal when evaluated in their last burn physician encounter. We suspect that after their last visit with a burn physician, their wounds had fully or almost closed. Therefore, there was little incentive for them to follow up in our burn clinic.

Pediatric pavement burns can be managed safely and responsibly in the outpatient arena without any major long-term sequalae. Future strategies can be focused on performing a deeper analysis of where geographically these injuries are occurring and if there is some commonality with these locations. This can further hone strategies focused on outreach and prevention of such injuries.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have no conflicts of interest and received no funding for this research.

REFERENCES

Kramer

CB

,

Rivara

FP

,

Klein

MB

.

Variations in U.S. pediatric burn injury hospitalizations using the national burn repository data

.

J Burn Care Res

2010

;

31

:

734

–

9

.

Harrington

WZ

,

Strohschein

BL

,

Reedy

D

,

Harrington

JE

,

Schiller

WR

.

Pavement temperature and burns: streets of fire

.

Ann Emerg Med

1995

;

26

:

563

–

8

.

Vega

J

,

Chestovich

P

,

Saquib

S

,

Fraser

D

.

A 5-year review of pavement burns from a desert burn center

.

J Burn Care Res

2019

;

40

:

422

–

6

.

Eisenberg

M

,

Chestovich

P

,

Saquib

SF

.

Pavement burns treated at a desert burn center: analysis of mechanisms and outcomes

.

J Burn Care Res

2020

;

41

:

951

–

5

.

Silver

AG

,

Dunford

GM

,

Zamboni

WA

,

Baynosa

RC

.

Acute pavement burns: a unique subset of burn injuries: a five-year review of resource use and cost impact

.

J Burn Care Res.

2015

;

36

:

e7

–

e11

.

Saquib

S

,

Carroll

J

,

Chestovich

P

.

Seasonal impact in admissions and burn profiles in a desert burn unit

.

Burns Open

2021

;

5

:

45

–

9

.

Clifton

T

,

Khoo

TW

,

Andrawos

A

,

Thomson

S

,

Greenwood

JE

.

Variation of surface temperatures of different ground materials on hot days: burn risk for the neuropathic foot

.

Burns

2016

;

42

(

2

):

453

–

6

.

Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Burn Association 2021.

This work is written by (a) US Government employee(s) and is in the public domain in the US.