Abstract

This case report describes a case of fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis complicated by both vanishing bile duct syndrome and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to Influenza B infection. Here we highlight the potential for complex morbidity secondary to underlying autoimmune hypersensitivity. Furthermore, the stepwise progression of these pathologies is noted, with the initial epidermal lesions first progressing to cholestatic injury and then subsequently to the hematologic manifestations.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are well-established T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity reactions affecting all age groups and are induced by a wide range of drugs or infectious agents. They are defined by characteristic dermatologic and mucosal sloughing lesions; however, there is also a slew of systemic manifestations. In this report, we present a rare and complex case of TEN complicated by both vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) resulting in multiorgan damage and eventual death. VBDS is the manifestation of several pathologies, including graft-vs-host disease, cystic fibrosis, or drugs, and presents as progressive destruction of intrahepatic interlobular bile ducts in which less than 50% retain patency. HLH is a rare disorder characterized by unregulated T-cell and NK-cell activation leading to shock or sepsis-like symptoms.

COURSE

A 26-year-old male without a previous history of injury or illness was transferred to our burn unit from an outside hospital (OSH) with biopsy-proven SJS. The patient reported taking acetaminophen for several days for fever symptoms 2 weeks prior to OSH admission with the recovery of this initial fever. He had taken this drug in the past without issue. A rash then developed 10 days before OSH admission which was followed by another subjective fever. He was admitted to the outside hospital for progression of these symptoms and prophylactic broad antibiotics (ceftriaxone and vancomycin) were initiated at this time. He was also tested and found to be positive for Influenza B. Due to up-trending leukocytosis and spiking fevers, ceftriaxone therapy was replaced by cefepime for more broad coverage alongside Tamiflu. Notably, the patient’s blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/Cr was 20/1.5 during OSH stay and both total bilirubin (>4 µmol/L) and liver function tests (LFTs) (>100 IU/L) were elevated.

On admission at our burn unit, the patient’s lab values were diffusely elevated with a white blood cell count: 20 × 109/L, platelets: 557 × 109/L, prothrombin time: 34.1 seconds, partial thromboplastin time: 36 seconds, alkaline phosphatase (ALP): 343 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 153 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 381 IU/L, and total bilirubin: 9.6 µmol/L. Furthermore, initial examination indicated an 80% TBSA rash with significant sloughing and 36% open wounds covering the entire circumferential trunk and shoulders. The patient presented with significant hemorrhagic crusting cutaneous lips; however, the oral mucosa was remarkably spared. In addition to the sloughing, scattered dusky plaques with central bullae were notable on arms, legs, and glans penis. Furthermore, basket-weave orthokeratosis with evolving full-thickness epidermal necrosis was identified which is consistent with TEN. Based on presenting features, SCORe of Toxic Epidermal Necrosis (SCORTEN) was 2, which equates to an associated mortality of 12.1%.

Multiple specialties were consulted including hepatology, gastroenterology, infectious disease, nephrology, rheumatology, pulmonology, and dermatology. Infectious disease workup for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, herpes simplex virus (HSV), epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and COVID-19 were negative. Autoimmune workup indicated anti-antinuclear antibody (ANA) mildly positive with 1:80 speckled pattern and anti-Sjögren’s-syndrome-related antigen A (SSA) which may be associated with TEN. Anti-smooth muscle antibody was negative and IgG/IgM was within normal limits, thus was not suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis. Furthermore, anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, anti-RNP, anti-Mi-2/Jo-1, cryoglobulins, anti-SSB, anti-p/c-ANCA, anti-C3, anti-C4, anti-TPO, and anti-MDA5 were within normal limits. On sonogram, hepatic parenchyma had a normal appearance and patent vessels.

The patient received our unit’s standard immunomodulation treatment protocol for TEN with etanercept and a 5-day course of IVIG as well as general supportive critical care and wound care. During the initial 2 weeks at the burn ICU, the patient was intermittently tachycardic and tachypneic due to metabolic acidosis requiring mechanical ventilatory support 4 days after admission. The patient’s condition was further impaired due to massive diarrheal fluid loss due to progressive bowel wall involvement of TEN. This resulted in a daily fluid loss of over 1 L and intolerance of enteral feeding for the first 3 weeks of admission. Loperamide was administered with improvement in symptoms; however, fluid loss precipitated the development of acute kidney injury and acute tubular necrosis. This required multiple days of continuous renal replacement therapy followed by intermittent hemodialysis. Both BUN and creatinine levels were persistently elevated with BUN averaging 60.78 and creatinine averaging 2.95.

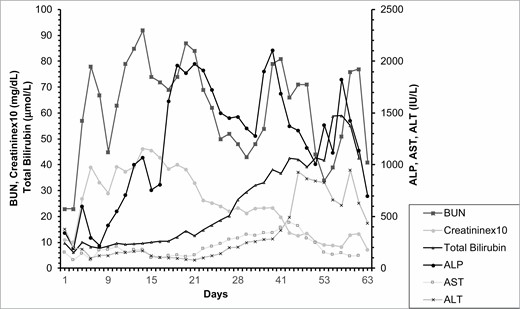

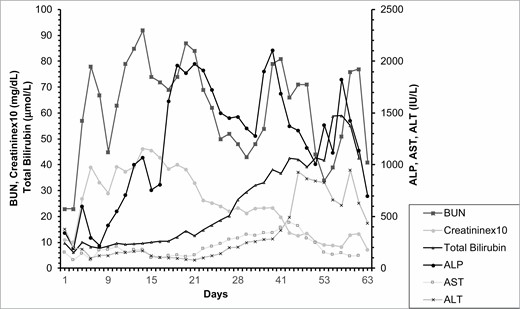

By hospital day 15, all open cutaneous lesions were closed however leukocytosis continued to worsen, which was followed by Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus positive bronchioalveolar lavage. He also had significant ongoing gastrointestinal symptoms with high output diarrhea, though the volumes were decreasing at this time. The patient self-extubated during this stage and was stably tachypneic to 30 seconds with respiratory alkalosis to PCO2 =25 and pH = 7.49. His LFTs remained markedly elevated, with AST, ALT, and ALP reaching 189, 102, and 1912 IU/L (Figure 1). Workup for this included repeated ultrasounds of his liver and a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography which was unable to visualize any intrahepatic duct dilation (Figure 2). He also had detectable fluid around his gallbladder, thus a cholecystostomy tube was placed due to concern for acalculous cholecystitis; however, this had very low output and did not change his liver function. Subsequently, liver biopsy indicated cholestasis and ductopenia, without portal fibrosis or inclusions, consistent with VBDS 21 days after admission which corroborated the increasing LFTs during this stage of admission.

Figure 1.

Progression of selected laboratory values representing disease progression. Creatinine values were multiplied by 10 for visualization purposes. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase.

Figure 1.

Progression of selected laboratory values representing disease progression. Creatinine values were multiplied by 10 for visualization purposes. BUN, blood urea nitrogen; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showing no evidence of intrahepatic bile duct dilation. Bile duct is normal in caliber and only periportal edema was appreciated.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showing no evidence of intrahepatic bile duct dilation. Bile duct is normal in caliber and only periportal edema was appreciated.

As the patient’s TEN lesions continued to heal without further complication, there were growing concerns for HLH due to elevated ferritin, triglycerides (TGs), and hepatosplenomegaly; however, fibrinogen remained elevated and liver biopsies were without lymphocytic infiltrates. The patient fulfilled the criteria for HLH at hospital day 18, with fever, splenomegaly, hemoglobin: 7.0 g/dL, ferritin: 5463 ng/mL, and TGs: 390 mg/dL; however, many of these measures could be explained due to liver dysfunction (ferritin), infectious etiologies (ALP and eosinophilia), and total parenteral nutrition (TGs). HLH was diagnosed on hospital day 37 with elevated levels of soluble IL-2 receptor and CT-guided bone marrow biopsy, revealing moderately hypercellular bone marrow with numerous histiocytes and hyperplasia of megakaryocytes, granulocytes, and erythrocytes. At this stage, ferritin levels had risen to over 35,000 ng/dL and TGs were over 900 mg/dL. Additionally, central nervous system involvement was suspected due to flat affect and cerebrospinal fluid was grossly icteric with nucleated cells and segmented neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes. A course of dexamethasone and reduced dose etoposide was initiated after bone marrow biopsy.

After 58 days at our hospital, the patient was transferred to an outside hospital for liver transplant evaluation with a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 25. On day 2 at this facility, the patient had a seizure likely related to either a new subdural hematoma that was found at that time, hepatic encephalopathy, or HLH. The patient was intubated after day 3 for airway protection given worsening acidosis and continuous renal replacement therapy was then started. At this time, he also showed severe decompensated liver failure with refractory acidosis and coagulopathy. He finally expired that day on hospital day 61 despite maximal medical interventions.

DISCUSSION

The specific etiology of foreign antigen-induced skin reactions such as SJS, TEN, or SJS/TEN overlap syndrome is still somewhat unknown; however, there are several hypotheses describing potential mechanisms of pathology. The underlying pathophysiology consistently links to an inappropriate adaptive immune response against keratinocytes via the actions of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, NK cells, and NK T cells which subsequently release damaging cytokines, thus killing keratinocytes.1 This process is likely initiated via interactions between immunogenic metabolites and HLA proteins or T-cell receptors which are then aberrantly bound and conformationally altered to be more disposed to autoimmune processes. These may be due to viral infection, of which human herpesvirus has been most frequently reported.2,3 As our patient was diagnosed with influenza B before the course of the TEN symptomology, this may be an important trigger. Interestingly, there have only been two reports of Influenza B-induced SJS or TEN and both were in pediatric patients who presented without gastrointestinal manifestations.4,5 Thus, here we may have one of the first reported cases of TEN associated with Influenza B infection in the adult population.

Various drugs have also been implicated in causing TEN, including allopurinol, anti-epileptics, antibacterial sulfonamides, sulfasalazine, phenobarbital, nevirapine, and oxicam NSAIDs (meloxicam and piroxicam).6 However, although our patient indicated the use of Tylenol during acute febrile illness, the timeline for TEN induction after drug intake does not fit, thus this specific cause is less likely.

Similarly, secondary HLH may arise due to strong immune activation due to a severe infection or malignancy. Of these etiologies, Herpesviridae infection is the most commonly implicated, with EBV accounting for the largest portion of these cases.7 This disease presents with numerous symptoms including fever, neurologic impairment, edema, liver dysfunction, dermatologic signs, and eventual progression to systemic illness and shock.8

A key component of this case is the sequential complication of TEN, VBDS, and HLH. Notably, both HLH and TEN seem to share common pathways of pathogenesis, particularly the induction of elevated serum granulysin and failure of T-cell autoregulatory pathways.9,10 SJS or TEN and HLH have been linked together within the literature, with several case reports describing such cases.11–13 Both of these diseases are relatively rare, with the overall incidence of SJS being one to six cases per million people per year with a mortality rate of around 5%, usually arising from complications related to liver or kidney damage or infection.14 Due to its broad manifestations, the true incidence of HLH in adults is not specifically known, although recent reports suggest it may account for up to 1 in 2000 adult admission at tertiary centers.15 With regard to the systemic manifestations of SJS or TEN, hepatitis is one of the more common manifestations, with 47% of patients with SJS having such symptoms; however, cholestatic injury is less common, with only a handful of cases reporting VBDS in association with SJS or TEN.16–18 The concomitant diarrheal fluid loss alongside systemic autoreactivity may have potentiated the risk for VBDS development in this patient. Mortality rates seem to be higher in patients with concurrent SJS or TEN and liver injury, with the Drug‐Induced Liver Injury Network reporting mortality of four out of nine patients with concurrent SJS and liver injury.19 Additionally, another report suggests that populations with high mortality have an underlying disease, with all six deaths in a case study of 88 patients having either a connective tissue disease, malignancy, or previous mesenteric necrosis.20 HLH has a relatively poor prognosis as shown in a recent large retrospective US cohort of 68 adults with HLH, 31% of patients were alive after 32.2 months of median follow-up; however, the median overall survival was only 4 months.8

Regarding the treatment of TEN, there is significant evidence in support of the simultaneous use of IVIG and TNF-alpha inhibitors, with a recent meta-analysis reporting that of 91 patients receiving TNF-alpha inhibitors, 86% responded well and were discharged.21,22 Additionally, there is evidence that the use of cyclosporine results in a significant reduction in mortality; however, this review also reported significant publication bias, thus further confirmation must be conducted in more statistically stringent trials.23 Furthermore, SJS or TEN complicated by VBDS has been successfully treated via ursodeoxycholic acid and early suppressive immunotherapy via high-dose corticosteroids and tacrolimus; however, there are no specific guidelines for these complications.16,24

In conclusion, we report a unique case of TEN likely secondary to Influenza B infection in an adult male, which was complicated by VBDS and HLH. Further studies are needed to establish specific factors that predispose individuals to the more lethal complications of foreign antigen skin reactions and to evaluate effective treatment options for these patients.

Funding Sources: None.

Conflict of interest statement. None.

Author Contributions: Conception of this report was performed by A.L. and J.W. Data collection was performed by J.W. Manuscript writing was performed by all authors. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

REFERENCES

White

KD

,

Chung

WH

,

Hung

SI

,

Mallal

S

,

Phillips

EJ

.

Evolving models of the immunopathogenesis of T cell-mediated drug allergy: the role of host, pathogens, and drug response

.

J Allergy Clin Immunol

2015

;

136

:

219

–

34; quiz 235

.

Chen

CB

,

Abe

R

,

Pan

RY

et al.

An updated review of the molecular mechanisms in drug hypersensitivity

.

J Immunol Res

2018

;

2018

:

6431694

.

D’Orsogna

LJ

,

Roelen

DL

,

Doxiadis

II

,

Claas

FH

.

Alloreactivity from human viral specific memory T-cells

.

Transpl Immunol

2010

;

23

:

149

–

55

.

Tamez

RL

,

Tan

WV

,

O’Malley

JT

et al.

Influenza B virus infection and Stevens–Johnson syndrome

.

Pediatr Dermatol

2018

;

35

:

e45

–

8

.

Goyal

A

,

Hook

K

.

Two pediatric cases of influenza B-induced rash and mucositis: Stevens–Johnson syndrome or expansion of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash with mucositis (MIRM) spectrum?

Pediatr Dermatol

2019

;

36

:

929

–

31

.

Hsu

DY

,

Brieva

J

,

Silverberg

NB

,

Silverberg

JI

.

Morbidity and mortality of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in United States adults

.

J Invest Dermatol

2016

;

136

:

1387

–

97

.

Smith

MC

,

Cohen

DN

,

Greig

B

et al.

The ambiguous boundary between EBV-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and systemic EBV-driven T cell lymphoproliferative disorder

.

Int J Clin Exp Pathol

2014

;

7

:

5738

–

49

.

Schram

AM

,

Comstock

P

,

Campo

M

et al.

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: a multicentre case series over 7 years

.

Br J Haematol

2016

;

172

:

412

–

9

.

Nagasawa

M

,

Ogawa

K

,

Imashuku

S

,

Mizutani

S

.

Serum granulysin is elevated in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

.

Int J Hematol

2007

;

86

:

470

–

3

.

Gao

Z

,

Wang

Y

,

Wang

J

,

Zhang

J

,

Wang

Z

.

The inhibitory receptors on NK cells and CTLs are upregulated in adult and adolescent patients with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

.

Clin Immunol

2019

;

202

:

18

–

28

.

Nic Ionmhain

UM

,

Knezevic

BR

,

Barraclough

A

,

Lucas

M

,

Anstey

M

.

What’s beneath the surface? Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis combined with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a case report

.

Anaesth Intensive Care

2017

;

45

:

125

–

7

.

Vengalil

N

,

Nakamura

M

,

Williams

K

,

Eshaq

M

.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome complicated by fatal hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

.

JAAD Case Rep

2019

;

5

:

857

–

60

.

Yamaoka

T

,

Azukizawa

H

,

Tanemura

A

et al.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis complicated by sepsis, haemophagocytic syndrome, and severe liver dysfunction associated with elevated interleukin-10 production

.

Eur J Dermatol

2012

;

22

:

815

–

17

.

Gerull

R

,

Nelle

M

,

Schaible

T

.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome: a review

.

Crit Care Med

2011

;

39

:

1521

–

32

.

Parikh

SA

,

Kapoor

P

,

Letendre

L

,

Kumar

S

,

Wolanskyj

AP

.

Prognostic factors and outcomes of adults with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

.

Mayo Clin Proc

2014

;

89

:

484

–

92

.

Li

L

,

Zheng

S

,

Chen

Y

.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and acute vanishing bile duct syndrome after the use of amoxicillin and naproxen in a child

.

J Int Med Res

2019

;

47

:

4537

–

43

.

Momen

S

,

Dangiosse

C

,

Wedgeworth

E

,

Walsh

S

,

Creamer

D

.

A case of toxic epidermal necrolysis and vanishing bile duct syndrome, requiring liver transplantation

.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol

2017

;

31

:

e450

–

2

.

Yamane

Y

,

Matsukura

S

,

Watanabe

Y

et al.

Retrospective analysis of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in 87 Japanese patients—treatment and outcome

.

Allergol Int

2016

;

65

:

74

–

81

.

Chalasani

N

,

Bonkovsky

HL

,

Fontana

R

et al. ;

United States Drug Induced Liver Injury Network

.

Features and Outcomes of 899 patients with drug-induced liver injury: the DILIN prospective study

.

Gastroenterology

2015

;

148

:

1340

–

52.e7

.

Wang

L

,

Mei

X-L

.

Retrospective analysis of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in 88 Chinese patients

.

Chin Med J (Engl)

2017

;

130

:

1062

–

8

.

Pham

CH

,

Gillenwater

TJ

,

Nagengast

E

,

McCullough

MC

,

Peng

DH

,

Garner

WL

.

Combination therapy: etanercept and intravenous immunoglobulin for the acute treatment of Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis

.

Burns

2019

;

45

:

1634

–

8

.

Zhang

S

,

Tang

S

,

Li

S

,

Pan

Y

,

Ding

Y

.

Biologic TNF-alpha inhibitors in the treatment of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a systemic review

.

J Dermatolog Treat

2020

;

31

:

66

–

73

.

Ng

QX

,

De Deyn

MLZQ

,

Venkatanarayanan

N

,

Ho

CYX

,

Yeo

WS

.

A meta-analysis of cyclosporine treatment for Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis

.

J Inflamm Res

2018

;

11

:

135

–

42

.

Garcia

M

,

Mhanna

MJ

,

Chung-Park

MJ

,

Davis

PH

,

Srivastava

MD

.

Efficacy of early immunosuppressive therapy in a child with carbamazepine-associated vanishing bile duct and Stevens–Johnson syndromes

.

Dig Dis Sci

2002

;

47

:

177

–

82

.

Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Burn Association 2021.

This work is written by (a) US Government employee(s) and is in the public domain in the US.